Remember the sound of a cassette tape loading, the static smell of a CRT monitor warming up, and the thrill of seeing a pixelated game title screen appear? For a whole generation in the United Kingdom and Europe, these sensory memories are inextricably linked to one name: Amstrad. In the colourful and chaotic world of 1980s home computing, where every brand promised a gateway to the future, Amstrad carved out a unique and enduring legacy. It wasn’t just a computer; it was a complete, affordable package that brought technology into countless living rooms. Today, let’s take a journey back to explore what made Amstrad special, why it mattered, and how its spirit lives on in the hearts of retro enthusiasts.

To understand Amstrad, you first have to understand the man behind it: Sir Alan Sugar. Long before he became a household name pointing fingers on The Apprentice, Sugar was a shrewd entrepreneur with a genius for understanding what the public wanted. His company, Amstrad (short for Alan M. Sugar Trading), started in 1968 selling car aerials and hi-fi stacks. His philosophy was simple but revolutionary for the tech market: give people everything they need in one box, at a price that doesn’t break the bank. While other computers required you to separately buy a monitor, tape deck, and even a power supply, Sugar saw the frustration in that. He knew the average family wanted simplicity. This “all-in-one” ethos became the beating heart of Amstrad’s most famous creation: the CPC series.

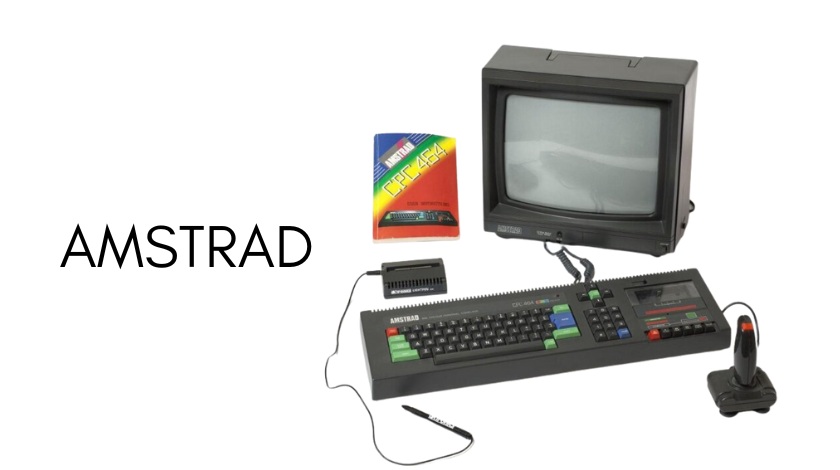

Launched in 1984, the Amstrad CPC 464 was a masterpiece of packaging. Open the box, and you had it all. The sleek grey keyboard housed the computer itself. Plugged into it was a dedicated, crisp green-screen monitor (or a colour one if you splashed out). And built right into the side was a cassette tape deck for loading games and programs. You just needed one power cable. For parents, this was a dream—no confusing arrays of wires and incompatible gadgets. For kids, it was a magic box of endless possibility. I vividly remember unboxing a CPC 464 at a friend’s house; it felt so much more substantial and “complete” than my own jumble of computer parts. The satisfying clunk of the giant rubber keys and the distinctive chirrup as it booted into Locomotive BASIC felt like the start of an adventure.

While the CPC was the games machine, Amstrad had another ace up its sleeve: the PCW, or Personal Computer Word-processor. Launched around the same time, this was aimed at a completely different market: small businesses, students, and writers. It came with a dedicated word-processing program, a daisy-wheel printer that produced typewriter-quality text, and again, that brilliant all-in-one design. The PCW was astoundingly successful because it solved a real problem affordably. Many a dissertation, novel, and small business letter was born on its green screen. This dual approach showed Amstrad’s breadth—they weren’t just selling toys; they were selling practical tools for work and play, all under the same trusted brand.

Ah, but the games! This is where nostalgia hits hardest. The Amstrad CPC, with its capable sound and vibrant colour palette, became a powerhouse for 8-bit software. Titles like Chuckie Egg, with its frantic egg-collecting action, Harrier Attack, with its simple but addictive bombing runs, and Dizzy, the loveable egg-shaped adventurer, defined countless childhoods. The soundtracks, composed within severe technical limits, are still instantly recognisable. The ritual of loading a game from tape was an event in itself. You’d type RUN" and press play, then wait for five agonising minutes as the screen filled with colourful stripes and the tape deck emitted a wild, robotic screech. A failed load meant rewinding and trying again, a lesson in patience modern instant downloads have erased! This shared experience created a deep, tactile connection to the software that is hard to replicate.

So, what happened? If Amstrad was so successful, why aren’t we buying Amstrad laptops today? The landscape shifted dramatically in the early 1990s. The era of the dedicated 8-bit home computer was ending, overtaken by more powerful and standardised IBM PC compatibles. Amstrad tried to adapt, producing its own range of PCs and even venturing into the doomed console market with the GX4000. They also made later versions of the popular ZX Spectrum, like the +2. But the magic formula of the all-in-one package became less unique as PC prices fell. The company pivoted, focusing on other consumer electronics and telecommunications, like the once-ubiquitous “emailer” phones. The home computer chapter had gracefully closed. Amstrad’s story isn’t one of failure, but of a company that brilliantly dominated a specific moment in time.

You might think that’s the end, but Amstrad’s legacy is vibrantly alive. Hop online, and you’ll find a thriving community of collectors, programmers, and fans. Websites are dedicated to preserving every game ever released. Emulators like CPCemu allow anyone to relive those classic moments on a modern PC or even a smartphone. For the truly dedicated, original hardware is lovingly restored—replacing leaky capacitors, cleaning dusty keyboards, and getting that old monitor to glow once more. There’s a beautiful respect for this piece of history. I recently attended a retro computing fair, and the buzz around the Amstrad tables was palpable. People weren’t just buying objects; they were sharing stories, reconnecting with a part of their youth, and introducing their children to the computers they grew up with. This isn’t just nostalgia; it’s preservation.

In the end, Amstrad represents something profoundly important: accessible technology. Sir Alan Sugar’s vision demystified computing. He took a complex, intimidating new world and packaged it in a way that felt welcoming and manageable for everyone. The Amstrad CPC and PCW weren’t the most powerful machines of their day, but they were arguably the most thoughtful. They understood the user’s fear and excitement. They bridged the gap between enthusiast curiosity and mainstream adoption. For that reason, Amstrad holds a cherished place in the history of technology. It was a truly British pioneer that, for a glorious few years, put the future within reach of millions, one all-in-one box at a time.

Conclusion

The story of Amstrad is a classic tale of innovation meeting market need at the perfect time. By focusing on user-friendly, complete packages, Sir Alan Sugar’s company captured the spirit of the 1980s home computing boom in a way few others could. From the game-filled halls of the CPC to the word-processing prowess of the PCW, Amstrad left an indelible mark on a generation. Its physical machines may now be relics, but its legacy—of making technology approachable, fun, and practical—resonates powerfully in today’s world. It reminds us that great tech isn’t just about raw power; it’s about understanding people and delivering what they truly need.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What does “Amstrad” stand for?

A: It stands for Alan M. Sugar Trading. It was founded by the now-famous entrepreneur and TV personality Sir Alan Sugar in 1968.

Q: What was the most popular Amstrad computer?

A: The Amstrad CPC 464 is the iconic model most people remember. Its all-in-one design with a built-in tape deck made it a huge hit in homes across the UK and Europe.

Q: Can I still play Amstrad games today?

A: Absolutely! You don’t need the original hardware. Software called an “emulator,” such as CPCemu or WinAPE, can mimic the Amstrad CPC on your modern computer, allowing you to run game files (often called ROMs).

Q: Did Amstrad make the ZX Spectrum?

A: Not originally. The ZX Spectrum was created by Sinclair. However, after Amstrad bought Sinclair’s computer business in 1986, they produced new models like the ZX Spectrum +2 and +3, which had built-in tape decks or disk drives, continuing the “all-in-one” theme.

Q: Is Amstrad still a company?

A: The Amstrad brand still exists, but it is no longer the force it was in the 80s. It is now a private company owned by Sir Alan Sugar’s family and has historically been involved in licensing and various technology investments, but it does not produce consumer computers like it used to.